Daniel Zauderer, 31, a 6th grade humanities teacher at the American Dream School, spent most of a recent evening trying to find transportation for an extra half pallet of produce at FoodFest Depot. Someone had to pick up the produce by 7 p.m. or it would be trashed. It took multiple phone calls through his network of volunteer drivers before he found someone with an SUV who could make the trip.

This is all part of Zauderer’s work as a lead organizer, or “fridgekeeper,” for the Mott Haven community fridge, one of the five open-access, volunteer-run public fridges in the South Bronx.

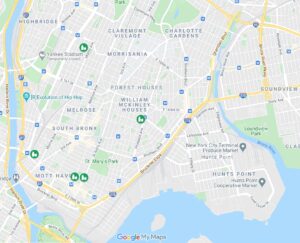

There are about 60 community fridges throughout the city, and eleven in the Bronx, including Mott Haven community fridge, at 141st St. and St. Ann’s, and the HP community fridge, which was originally on Hunts Point Avenue before being moved to 15 Canal Place.

Rhina Diaz, 39, lives just a block away from the Mott Haven fridge and visits every day to help clean the fridge and pick up items for her family of four. She particularly likes when there are vegetables from nearby community gardens.

“A lot of people have been motivated to leave something. It’s really great to see people want to do something to benefit other people,” said Diaz in a phone interview translated from Spanish by her nephew, Michael Hernandez.

One of the biggest hurdles of finding a fridge (usually donated or purchased secondhand) and a host location (often a local business) willing to provide electricity, a network of loosely connected activists, organizers, drivers, volunteer cooks and cleaners keep the South Bronx community fridges stocked and clean.

Zauderer , who runs the fridge with fellow teacher Charlotte Alvarez, says he spends at least 30 hours a week making phone calls, building partnerships with food distributors, organizing cleaning schedules and finding volunteers with cars.

Problems are dealt with as they come. If a fridgekeeper needs storage space, someone to build a pantry or even help moving a fridge down the street (as was the case with Zauderer several weeks ago), they send messages to volunteer groups or community fridge supporters on social media and apps like Slack and Signal, hoping volunteers respond.

The volume of need in the area keeps the operation constantly abuzz. Diaz says the fridge is almost empty most nights.

Before the pandemic, the Hunter College NYC Food Policy Center reported in their 2020 Foodscape that 20.9% of Mott Haven and Melrose residents experience food insecurity, and 52% of households in these neighborhoods receive SNAP benefits.

According to Charles Platkin, executive director of the center, these numbers have undoubtedly grown as a result of the pandemic.

Zauderer has been thinking about changes that could help the Mott Haven fridge run more self-sufficiently without as much organization and oversight. But for now, he’s focused on keeping the fridge cleaned and stocked.

Like other South Bronx fridgekeepers, Zauderer doesn’t expect to end hunger. Instead, they hope community fridges can draw attention to conversations around food access and provide some relief within the system that currently exists.

“It’s not about solving food insecurity with one thing,” says Zauderer. “It’s about challenging the way things are done and thinking about the way that things could be done more sustainably. What are some bridges that can lead us toward that? What are some temporary solutions that might help?”