Residents aired their frustrations surrounding open-air drug use to the police during Melrose’s quarterly Build the Block meeting on a Thursday in September, at Mt. Bethel Baptist Church in Melrose. Officers Argenis Rosado and James McGuire, the two police officers assigned to Precinct 40-C, listened to what community members had to say, while explaining the limitations of the system.

The mood in the room seemed rebellious.

“We understand you’re doing the best you can,” Marty Rogers, 63, a frustrated retiree and frequent meeting attendee, told the officers. “But all our resources are being sucked down the drain by this drug stuff.” Rogers is especially incensed by the presence of drug users who gather outside his church, Immaculate Conception, on E 150th Street. Rogers is on the parish council and helps out with the music.

He shook his head.

“Our neighborhood is the hub of heroin; it’s Home Depot.”

The South Bronx does have a very high rate of heroin dependence; last year The New York Times reported that if the neighborhood was a state, it would have the second highest incidence of drug overdose death in the country, the majority of which are due to heroin. Additionally, Melrose is the former home of “The Hole”, the homeless encampment which was infamous for its residents’ outdoors drug usage.

The Hole was raided and emptied out by the de Blasio administration after a 2017 NY Daily News exposé, but residents like Rogers believe that the problem might have gotten worse as a result, as the addicts who used to shoot up near the train tracks now shoot up in front of Melrose’s schools and churches.

Or to put it in Rogers’ terms: “de Blasio closed The Hole–The Hole moved here.”

Isaac Hernandez, a former heroin user and community advocate who is in charge of the needle exchange program for Harlem United, a community-based healthcare and housing provider, says that a little more compassion is needed for those who currently use drugs. “People get in these situations where the drug use is more important than housing or food, but that’s not because they want to be like that. The first time that somebody does something, it’s a choice, but when you get addicted, that becomes your livelihood and your life.”

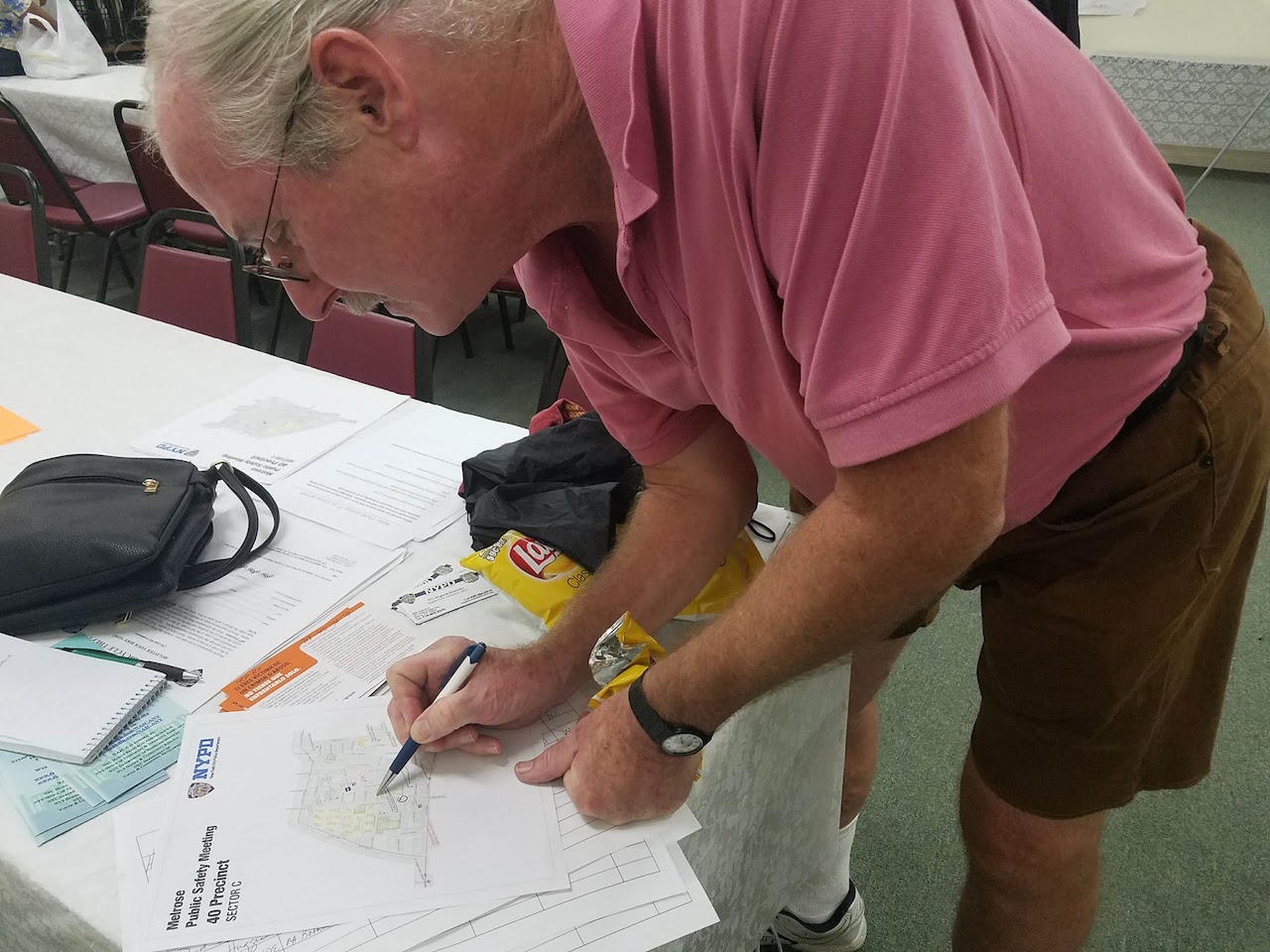

As residents described the drug activity they saw every day in front of their homes and churches, McGuire noted down the most problematic intersections for drug sales and use on an easel. (One of these hot-spots for drug use? The soon-to-open Roberto Clemente Plaza.)

“Any complaints you might have, we can work on them,” promised Rosado. But he too seemed frustrated with law enforcement’s inability to stop the problem of open-air drug usage. “It’s a never-ending cycle. You arrest someone today, they’ll be on the street tomorrow,” Rosado said.

And arresting people for drug use—that too is less simple than it used to be. Short of shooting up in the presence of a police officer, it’s harder for law enforcement to legally ascertain who is committing a crime. “You can’t arrest someone for loitering,” he said, to a surprised audience.

McGuire continued. “We can’t just search backpacks unless there’s a reasonable suspicion of possession of a weapon.”

The discussion turned to the impending (according to the officers) legalization of marijuana in the state, and the current decriminalization of the drug. “Now you can be walking down the street smoking a marijuana cigarette and you just get a summons,” said Rosado, to incredulous laughter from the residents. “Weed laws have changed, and not for the better,” he said.

When asked for comment, the NYPD said that “Officer Rosado was addressing community complaints about marijuana sales at a specific location” and that broad generalizations about how Rosado feels about shouldn’t be made regarding the statement. In August, the NYPD declared that officers now have discretion to either arrest or issue a ticket to a person using marijuana in public, depending on the person’s criminal record and whether they choose to cooperate or not.

When a resident asked if Melrose could expect a return of the beat cops that once patrolled the neighborhood, Rosado pointed at himself. “That’s us!” he said, laughing.

“You’re not going to see a return of cops on the street,” explaining that Operation Impact, the data-driven form of policing which had rookie cops routinely policing high-crime areas, had been dismantled, as it had been thought to lead to over-policing, which worsened relations between community members and the NYPD.

Instead there has been a gradual move towards “neighborhood-based policing”, where more experienced officers (like Rosado and McGuire), are tasked with becoming involved in the life of the community, rather than simply policing it.

The story was updated on Oct. 3.